In 1913, the World’s Fair held in the Flemish city of Ghent, Belgium, was intended to promote the merits of Belgian colonisation in Central Africa. This colonisation had begun in 1885, following the Berlin Conference, when Leopold II, the second King of the Belgians, succeeded in persuading his European rivals to grant him the ‘central basin’, a territory of 2,345,000 km² that would become his personal property. He often reminded people that the Congo had been acquired with his own funds, while conveniently omitting the fact that he had also benefited from a loan granted by the Belgian state.

Above all, the brutality of the conquest had sparked fierce criticism, mainly in the Anglo-Saxon world, fuelled by reports published in the British and American press. These accounts described in detail the corporal punishment, the forced labour imposed on the indigenous population, and the severed hands of those who resisted. Photographs documenting these practices circulated across Europe and tarnished the reputation of a country barely a century old.

In response, a First World’s Fair was held in Brussels in 1897 to present a more ‘positive’ side of colonisation. Belgian public opinion would above all remember that Congolese natives brought to Belgium were put on display for gawking crowds in freezing cold conditions. Nine of them succumbed to illness and were hastily buried in a section of the Tervuren cemetery (a town near Brussels) that had until then been reserved for prostitutes.

In 1908, the king finally ceded the Congo to Belgium. The government of the time accepted the offer with some reluctance: in its view, the colony tainted by numerous scandals was not to entail any expense for the metropole. Two years later, in 1910, the Palace of the Colonies was inaugurated in Tervuren. The building, designed by the French architect Charles Girault after the model of the Petit Palais in Paris, had been commissioned by Leopold II and paid for out of his personal coffers with profits derived from the Congo.

To Erase the Scandals as Quickly as Possible

Eager to respond once again to international criticism and to overcome the reluctance of a sceptical Belgian public, the Ghent World’s Fair of 1913 was intended, once again, to highlight the ‘civilising mission’ carried out in the Congo and to showcase the economic ‘development’ of the territory as well as the work of the missions.

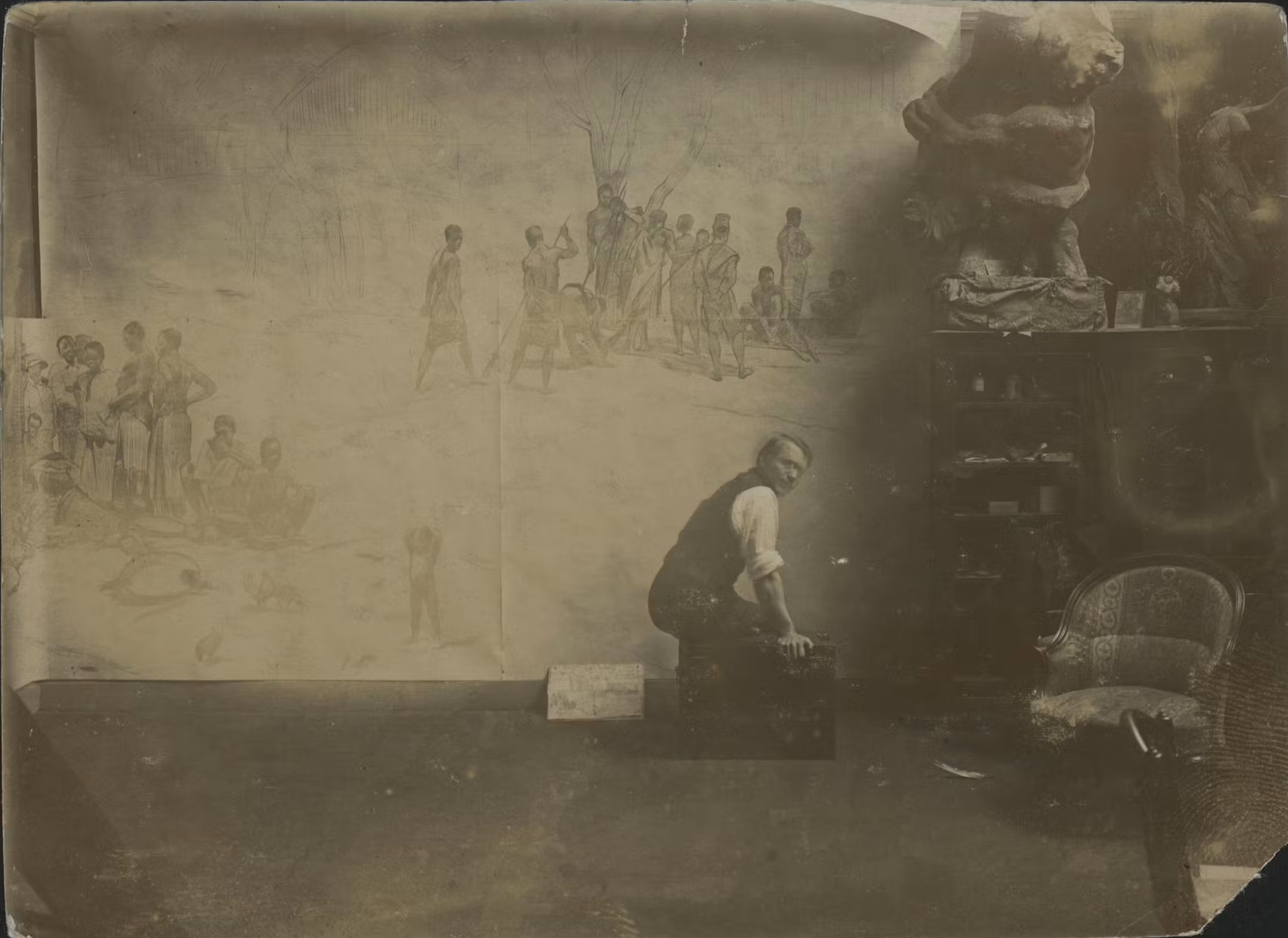

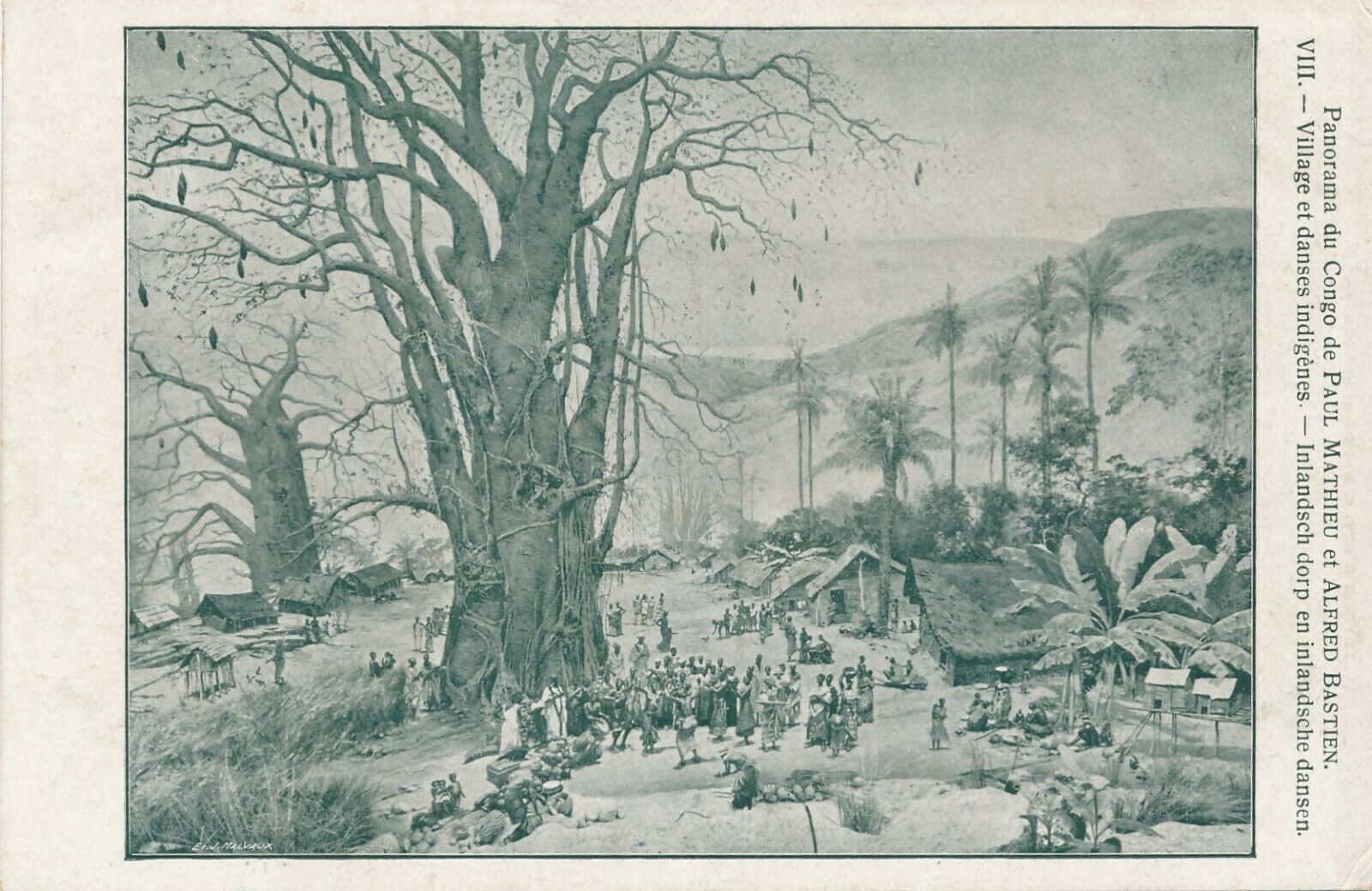

It was in this context that the monumental work Le Panorama du Congo was commissioned by a circular painting measuring 115 metres in length and 14 metres in height, which went on to attract large crowds. It was produced by two of the finest Belgian painters of the time, Alfred Bastien and Paul Mathieu. For the sake of balance, one was Catholic and the other a Freemason.

The Minister of Colonies, Jules Renkin, had proposed to them a year earlier to travel to the Congo and visit the port of Matadi. This port, located at the mouth of the Congo River, was the departure point for merchant ships crossing the Atlantic carrying ivory, rubber, and bales of cotton. Le Panorama du Congo was allocated a budget of 123,000 Belgian francs, a considerable sum for the time, equivalent to twelve years of work for a Belgian labourer.

With only eight weeks to survey the sites from the port of Matadi to the capital, Léopoldville – today’s sprawling Kinshasa – Paul Mathieu and Alfred Bastien confined themselves to the river’s mouth and its banks, without idling: from their survey, they brought back 150 photographs, 70 sketches, as well as recordings of Congolese voices captured on wax cylinders, the ‘phonographs’ of the time. Back in Belgium, the two painters were assisted by other artists, including Charles Léonard, Armand Apol, and Adrien Schultz.

“The Pavilion of the Severed Hands”

During the exhibition, housed in a pavilion of oriental-style architecture, visitors were directed to an observation balcony from which they could view a colourful, idealised Congo, perfectly illustrating the intentions of the exhibition organisers and the desires of the Minister of Colonies: to demonstrate the transition from barbarism to civilisation.

After captivating crowds in Ghent, the work was exhibited a second time at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1935. This would be its last public appearance. Subsequently, the immense canvas was carefully rolled up and stored in a cylinder at the Palace of Colonies in Tervuren, and later at the Army Museum, located in the Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels. This other symbolic site overlooking the ‘lower city’ had been created for the 50th anniversary of Belgium’s founding, opposite the ‘Pavilion of the Severed Hands,’ another building sarcastically renamed by the socialist leader Émile Vandervelde, as it had been funded with money from the Congo.

Le Panorama du Congo was damaged during the Second World War: The German occupiers pierced its casing, fearing it might contain shells… Despite efforts by the Ministry of Colonies and Leopold II’s heirs, the ‘colonial work’ never gained unanimous approval in Belgium. No one took care to repair or exhibit the piece, which had definitively fallen out of fashion.

Reconsidering “Le Panorama” With a Contemporary Perspective

It was not until 2022 that the work was digitised and its historical significance came to be recognised. The reproduction of the canvas, on display at the Tervuren Museum since 28 November, is nine times smaller than the original. Large sections of the latter are nevertheless exhibited in rooms located in the museum’s basement, without commentary, opposite a 22-metre-long dugout canoe and a small space devoted to the denunciation of racism.

The exhibition demonstrates how, over time and in response to criticism, the institution’s current mission has charged profoundly: it is no longer about illustrating Belgium’s “civilising mission” in the Congo, but about introducing visitors to Central Africa (the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi), which has been profoundly marked by Belgium’s influence.

The scholars responsible for curating the exhibition therefore re-examined “Le Panorama” through a contemporary lens. They recalled that, beyond its artistic qualities, it was above all a work of propaganda.

Aware that the two artists invited to the Congo by the Ministry of Colonies had not merely admired the beauty of the immense river, the majesty of the landscapes, or the bustle of the markets, today’s specialists also delved into the museum’s archives. In this way, they unearthed the photographs and sketches brought back by the painters to inspire their compositions. They also copied and digitised the recordings that had lain dormant in trunks for a century.

The Hidden Reality Behind the Images

The truth did not take long to come to light. On the surface, painters had focused only on the bright colours of the loincloths and markets, the lively discussions where locals met Europeans in uniform, the majesty of merchant ships and the feat of engineering that was the construction of the “Cataract Railway” to connect the port of Matadi to Leopoldville.

In fact, unearthed and revived contemporary techniques, the artists’ photos tell a very different story: in the background of the seemingly peaceful discussions, the images show conscripts from the Congolese Public Force, the army of the time, lurking in the bushes. With a threatening attitude, they stand ready, at the slightest gesture from the Belgian officers, to open fire on a crowd that is less serene than it appears.

The translation of the recordings from the period confirms the unease. To study them, the researchers had to leave Kinshasa and travel to Ituri and Maniema, regions in the east of the country where, in the wake of slave traders coming from the shores of the Indian Ocean, many porters had once been recruited. The scholars asked villagers – especially the elders – to listen, with a century’s distance, to the grievances that their ancestors had entrusted to the recording devices of the time.

“Our Father Chose to Stab Himself”

Congolese people today were then able to translate the laments, the cries from the past. Where colonisers believed they heard nothing more than traditional melodies, other messages had been woven in behind the beating of the drums. With headphones on, visitors at Tervuren now listen to the reality of these voices from another time: ‘There is nothing left here, except suffering,’ ‘the fire destroyed everything,’ ‘the village has been abandoned,’ ‘all we have left are poisoned arrows,’ ‘if you are too weak, you will be whipped,’ ‘our father was taken by force, but he chose to stab himself’. These complaints finally expose the true face of the so-called ‘model colony.’

It also emerges that the famous ‘Cataracts Railway,’ built by Senegalese workers and by Chinese ‘coolies’ who replaced failing Congolese labourers, was not intended to transport passengers, except for Europeans. Others were required to walk alongside the railway tracks, as only goods ‘went up’ toward the capital, Léopoldville, or ‘went down’ toward the port of Matadi, with Antwerp as their final destination.

It is confirmed that when they described the ivory tusks unloaded from ships and piled up on the docks of the port city, Joseph Conrad and the historian Edmund Morel were not victims of hallucinations, and that their account of the 1,500 hands handed over to a Belgian officer following a ‘palaver’ that had gone badly was nothing but a terrible truth.

“Encampment of Naked, Shivering Africans”

The travel notes of the two painters, until now preserved in the museum archives and finally brought to light, also reveal another reality, far removed from the commissioned work.

They describe a “camp of naked, shivering black people”, “sheep that seem to be grazing on stone” and “a sick Senegalese man wrapped in a white boubou”. They reveal that the pretty straw huts that occupy the centre stage are nothing more than a backdrop, “chimbeques” or huts “built on foundations made of empty bottles”.

This exhibition, modest in size but with a powerful message, debunks all the cliches that have long fuelled the Belgian imagination, consisting of smiling black people and well-behaved children gathered in front of Catholic and Protestant missions.

Falsified Images and Biased News Reports

The current director of the museum, former diplomat Bart Ouvry, recalls that “The Panorama of the Congo was a work of propaganda that long convinced Belgian public opinion of the “benefits” of colonisation”. Implicitly, the current exhibition also revives the memory of the speech given by Patrice Lumumba on Independence Day, 30 June 1960.” “We have experienced irony, blows, insults…” Accused on that occasion of insulting the King of Belgium, who rose to his feet so as not to have to hear any more, the Prime Minister of Congo had then incurred the definitive wrath of the metropolis. Six months later, with Brussels’s approval, the hero of independence was handed over to his Katangan enemies, who executed him without hesitation.

For those who might still have doubts, it is now clear, with images and recordings to back it up, that colonial propaganda, whether from Belgium or other former colonial powers, was what we would today call “fake news”. Fake images and biased reports hark back to what was known as the “civilising mission” and remind us that the colonisation of Congo was above all an enterprise of economic exploitation, then referred to as development”.

Years have passed, but current images of children working in copper or cobalt mines, digging tunnels or carrying heavy loads show that this exploitation continues. Now, it is in Washington that the fate of Congo seems to be playing out, in the wake of the ”deal” imposed by Donald Trump, who intends to take away China’s access to strategic minerals and force Kinshasa to share its resources with neighbouring Rwanda, which acts as a fence and intermediary. In the current context of predation, violence and global indifference, Le Panorama du Congo, a work of trompe l’oeil, seems very topical.