Will the page ever turn? On the eve of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) 65th independence anniversary celebration this June 30th, the ghost of Patrice Lumumba, the ephemeral Prime Minister assassinated in 1961, resurfaces.

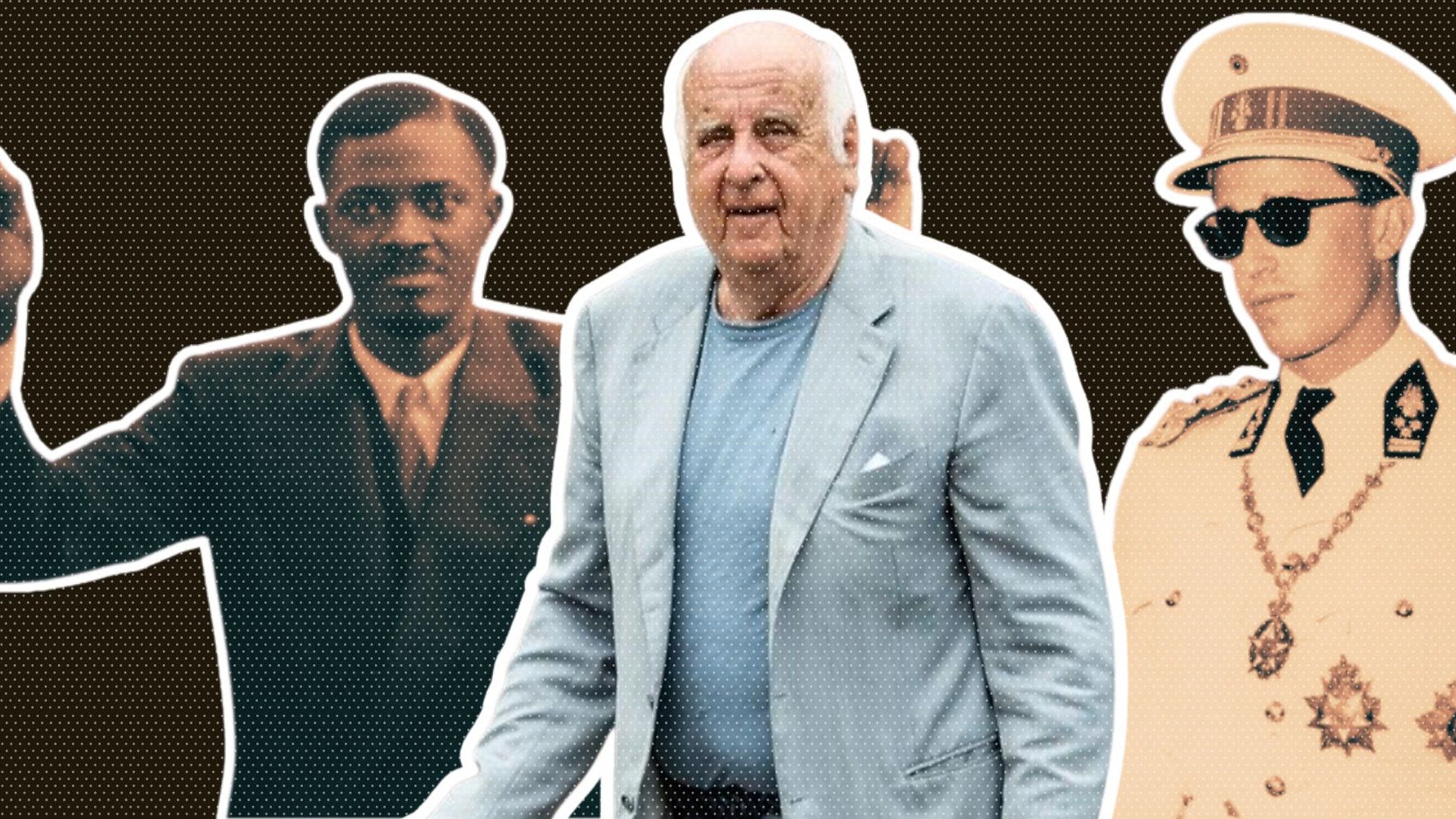

In a surprising turn of events, the Belgian federal prosecutor’s office has requested that one of the last remaining figures involved in the tragedy surrounding the independence of the former Belgian colony, Count Étienne Davignon, 92, be sent to the Brussels Criminal Court. He is expected to appear on January 20, 2026. In its indictment, the prosecution asserts that Davignon, who was then a young diplomatic intern in Kinshasa and later Brazzaville, had knowledge of the plan to arrest Patrice Lumumba. The Belgian aristocrat is accused of “unlawful detention and transfer of a prisoner of war,” “deprivation of the right to a fair trial,” and “inhuman and degrading treatment.” The intent to kill was not upheld, and a dismissal on that specific charge was requested.

A race against time has begun: the family, including whistleblower nephew Jean-Jacques Lumumba, believes that “Belgium allowed those responsible time to disappear.” The accusation will undoubtedly recall that the circumstances of Patrice Lumumba’s death are part of the history of the DR Congo: the Prime Minister, elected in May 1960 and confronted with an army mutiny in which Joseph Désiré Mobutu became commander-in-chief, was dismissed on September 5th of that year.

Lumumba was hunted down and imprisoned. He would escape, but was recaptured by Mobutu’s army, guided by the Americans and supported by the Belgians. The memory of the pursuit of Lumumba and his two companions, Minister of Youth Maurice M’Polo and Senator Joseph Okito, left its mark on the country.

The Cold War and the hunt for communists

His adversaries were too numerous: the people of Kasaï had not forgiven him for suppressing their uprising, while the Katangans, led by Moïse Tshombé, a former businessman endorsed by the all-powerful Union Minière du Haut Katanga, dreamed of secession, encouraged by certain Belgian circles and by the French who were eager to regain a foothold in a country that had slipped from their grasp during the Berlin Conference in 1885.

Above all, the former Belgian colonizer, represented by King Baudouin, heir to Leopold II, harbored a tenacious grudge against a man who, on June 30, 1960, during the independence ceremonies, delivered a memorable speech—foundational in the eyes of his people, insulting in the eyes of the colonizers: “We have known ironies, blows, and insults; the law was never the same whether we were white or black...”

This indictment against colonialism had fatal consequences: he, who had never traveled to the Soviet Union and whose Belgian friends were more liberal, was suspected of communist sympathies, which, in those Cold War times, was the equivalent of a death sentence. Patrice Lumumba’s painful journey ended in Katanga, where he was transferred in January 1961.

Ludo de Witte’s book awakens memories

Lumumba and his two companions, Joseph M’Polo and Okito, were beaten to death during the flight, to the point that the Belgian crew closed the communication door to the cockpit to avoid further disturbance. The detainees were transferred to a Belgian’s villa, the Brouhez house. Katangan dignitaries spent the night insulting and beating them until, the following morning, severely wounded and staggering but still standing, the three captives were taken to a clearing and shot.

Since the 1960s, after Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, the treacherous friend, became the ’Supreme Guide’ of a country renamed ’Zaire,’ the killing of Lumumba and his companions – a kind of founding crime – has become part of African history.

In Belgium, the case had long been considered closed. Despite sporadic press articles, a few books, and reminders from Lumumbists who had sought refuge in Belgium, the Belgian witnesses and actors involved in the Prime Minister’s descent into hell enjoyed prosperous and peaceful lives. This continued until the publication of a book that was not an academic thesis or a soothing, tedious work, but the product of a genuine investigation led by Ludo de Witte. At the time, de Witte was a Belgian civil servant, but more importantly, a tireless researcher and a man of the left. Soberly titled “L’assassinat de Lumumba” (Karthala), the book reawakened failing memories and set off a firestorm.

The killing, followed hour by hour

With great precision, he demonstrates that Belgian citizens—military personnel, civilians, civil servants, and diplomats—followed the prime minister’s murder hour by hour. Among other sordid details, the stunned public learned that the bodies, initially buried near the crime scene, were later transferred further away, dismembered with a chainsaw, and dissolved in an acid bath to erase all physical traces of the crime.

This information marks the beginning of another story, one as Belgian as it is Congolese: convened at the turn of the year 2000, a parliamentary commission of inquiry worked with the caution of a speleologist, listening to numerous testimonies shedding light on the responsibilities of Belgian nationals, but excluding from its scope of investigation the context of the Cold War and the involvement of other actors, including the United States and the CIA, who collaborated closely with their counterparts in Belgium.

At the conclusion of the parliamentary commission’s work, Belgium, through its Minister of Foreign Affairs Louis Michel, apologized to the families of the three deceased. After making promises of compensation through a foundation, the liberal minister declared that this time, the page had been turned.

Two teeth pulled from Lumumba

The story isn’t over, however. Gérard Soete, one of the soldiers tasked with making the bodies disappear, insisted on taking a macabre “souvenir”: two teeth pulled from Lumumba, one of which, according to him, was thrown into the North Sea. The other, carefully preserved, was seized in 2016, placed in an envelope, and deposited in a drawer at the Brussels Public Prosecutor’s Office.

In 2018, Belgium supported Félix Tshisekedi, who replaced Joseph Kabila after a controversial presidential election. The new leader in Kinshasa considered Belgium his “other Congo.” When Lumumba’s family requested the repatriation of Lumumba’s remains, no one objected. In these times of reconciliation, it would have been inappropriate to recall that Félix Tshisekedi’s father had not always been a fierce opponent of Mobutu and had signed Patrice Lumumba’s arrest warrant as Minister of Justice. And Belgian Prime Minister Alexander de Croo willingly cooperated.

But to top off the absurdity, the mausoleum built in Kinshasa, near the Limete interchange, poorly maintained and guarded, was robbed. According to authorities, Lumumba’s ’remains’ were transported elsewhere as a precautionary measure.

Davignon, a pure product of the establishment

After these acknowledgments, there was no longer any question of speculating about King Baudouin’s possible responsibility in the decision to eliminate Lumumba. The parliamentary commission of inquiry had only touched upon the issue: it had merely noted that when the plan appeared in a memo submitted to the King, the latter, who initialed all pages of the document, had expressed no objection.

It was also decided not to push for a full interrogation of the two surviving Belgian witnesses, Jacques Brassinne and Étienne Davignon. Brassinne was in Katanga as a colonial official when Patrice Lumumba and his companions arrived. He later spent years writing his memoirs and preparing a meticulously documented doctoral thesis that portrayed the Belgians in Katanga as helpless spectators of a tragedy whose scale and consequences were beyond them. This commendable effort was rewarded with his ennoblement.

As for Étienne Davignon, he literally slipped through the cracks and always refused to explain anything. And for good reason: a young diplomatic intern, 28 years old at the time of the events, he had been sent as reinforcement to Kinshasa on the eve of independence, then dispatched to the Belgian embassy in Brazzaville. The DRC had only been the first stop in a long and prestigious career that would make him one of Belgium’s most prominent figures. Étienne Davignon is a pure product of the Belgian establishment. His personal journey recalls the time when the small country was both rich, respected, and, regarding the DRC, highly regarded by the Americans.

A family close to the King

In a memoir (Étienne Davignon, Souvenirs de trois vies, Racine editions, 2019), the man who received the title of count vividly recounts the career of a well-born and gifted individual who led three equally successful lives: in diplomacy, at the European Commission, and in business.

This man, overflowing with charisma and social grace, is the son of diplomat Viscount Jacques Davignon. His father accompanied King Leopold III (1934-1951) when the latter traveled to Berchtesgaden to meet with Adolf Hitler, an act for which he was later criticized. His mother, born de Liederkerke, was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elisabeth, widow of King Albert (1909-1934) and the founder of the prestigious ’Queen Elisabeth Competition’ (Concours musical international Reine Élisabeth de Belgique).

Schooled in Catholic colleges, a graduate of the University of Louvain, and from a good family, it was only natural that the man known as “Stevie” would choose a career as a diplomat. As an intern, but armed with a solid network of contacts, he found himself before the age of 30 in a newly independent country for which he was unprepared.

“We didn’t know”

In his work, Étienne Davignon emphasizes that at the time, decisions concerning the Belgian Congo were primarily the responsibility of the Minister of African Affairs, Harold d’Aspremont Linden, rather than his direct superior, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Pierre Wigny. The two men, however, had no political disagreements.

Subordinate and perhaps an intern, but certainly a trusted aide: the young diplomat attends the June 30th ceremony in Léopoldville (the future Kinshasa) and observes that King Baudouin, after delivering “an incredibly paternalistic speech,” is “white with rage” when Lumumba delivers his speech, deemed “insolent and aggressive.”

As the unrest led to the hasty departure of the Belgians, Davignon remained very discreet about his role during the pursuit and subsequent assassination of the deposed Prime Minister: “In Belgium, at the Prime Minister’s office or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, we didn’t know he [Patrice Lumumba, Editor’s note] was dead. A month later, we landed in Elisabethville [now Lubumbashi, Editor’s note], on the day of the official announcement of his death.”

The amiable viscount has thrived in the establishment

While he claims he knew nothing, Davignon nevertheless introduces the awkward question: ’And did the Royal Palace know?’ He particularly wonders if Major Guy Weber, close to Moïse Tshombe and an officer of the King, had informed the sovereign of what was being prepared.

The documents unearthed by the parliamentary commission of inquiry have already answered his question: they indicate that the Head of State was aware, at least once, of a letter addressed to his chief of staff by Major Weber, who asserted that Lumumba’s life was threatened. This information did not elicit any reaction. It’s true that the letter, carefully read by the King and initialed on each page, mainly discussed his upcoming marriage...

The recent questioning of Étienne Davignon regarding a long-standing but unforgotten issue has caught the attention of the Belgian establishment, an environment in which the amiable viscount has thrived. After his African ventures, “Stevie” served as political director at the Foreign Affairs Ministry until 1976 and played a significant role within the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). He also held the position of Vice-President of the European Commission, responsible for the internal market and industry. In 1985, as a member of the Board of Directors of the Société Générale de Belgique, he heavily influenced the decision for the venerable holding company—which owed so much to the Democratic Republic of Congo—to fall under the control of the French company Suez, thereby escaping the grasp of Italian businessman Carlo de Benedetti.

Rewarded for service rendered?

Solvay, Sofina then Petrofina, Union Minière which became Umicore… It was also Davignon who, after the bankruptcy of the national company Sabena, launched Brussels Airlines. He was also found at the head of the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, the Spa-Francorchamps motor racing circuit, and numerous other institutions, not to mention the Trilateral Commission and many European foundations.

If he appears before a Brussels judge, Étienne Davignon will have to summon memories from his youth. He might be asked if the countless promotions that marked his long career weren’t partly a token of gratitude for services rendered during his African years.

Patrice Lumumba’s family, who will be present at the trial, will explain why they insisted, until the very end, that Étienne Davignon finally can tell “his” truth. Jean-Jacques Lumumba already emphasizes: “It was Congolese democracy that was beheaded with Lumumba’s assassination; Congo still suffers from it today. The fact that this democracy was halted in its early stages plunged the country into the chaos we still know.”

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism: