In Niger, the “Yellow Cake” is an unending source of topics and fantasies, especially when the issue of uranium extraction and exploitation intersects with French imperialism. Everyone has an opinion on the matter and it is widely accepted that this imbalanced relationship only benefits France. “The French have electricity thanks to Nigerien uranium, while 90% of Nigeriens do not have electricity” which is a commonly heard statement in Niamey, Zinder and Agadez. That may be true but factually exaggerated. According to the World Bank, 19.5 % of the population had access to electricity in 2022, and Nigerien uranium is not the only fuel powering French nuclear plants (around 15 % of France’s electricity comes from it, as we will see in the next article).

Nevertheless, this statement summarizes a widely shared viewpoint regarding a situation deemed scandalous and anachronistic. It is often accompanied by claims that are difficult to verify, asserting that Orano (and before it Areva, and even earlier, Cogema) is making a profit on the backs of the Nigeriens. To this, the multinational’s leader responds, in unison with French diplomats, that in reality, the Arlit mines are not that profitable. In the opaque world of mining extraction, disinformation is prevalent. And it is all the more difficult to establish a truth since what may have been accurate at one time – regarding production costs, purchase price s, the benefit Niger derives from it, etc. – may no longer be true at another time and could become so again later, depending on market changes or regulations, while the exploitation of Nigerien uranium has been ongoing for over fifty years.

What exactly is the situation? What is the significance of Niger’s uranium in French electricity production ? What does it represent in the Nigerien state budget ? And, above all, are the agreements between the French company and Niger really as unbalanced as they seem ?

To answer these questions – or attempt to, with the available open – source information – Africa XXI has examined reports from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the databases of the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), and Niger’s Treasury accounts since the 1970s and cross-referenced them with the financial statements of the French firm, the reports from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), and those of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on the changes in prices of uranium and the quantities officially produced by Orano.

3,000 tonnes per year on average

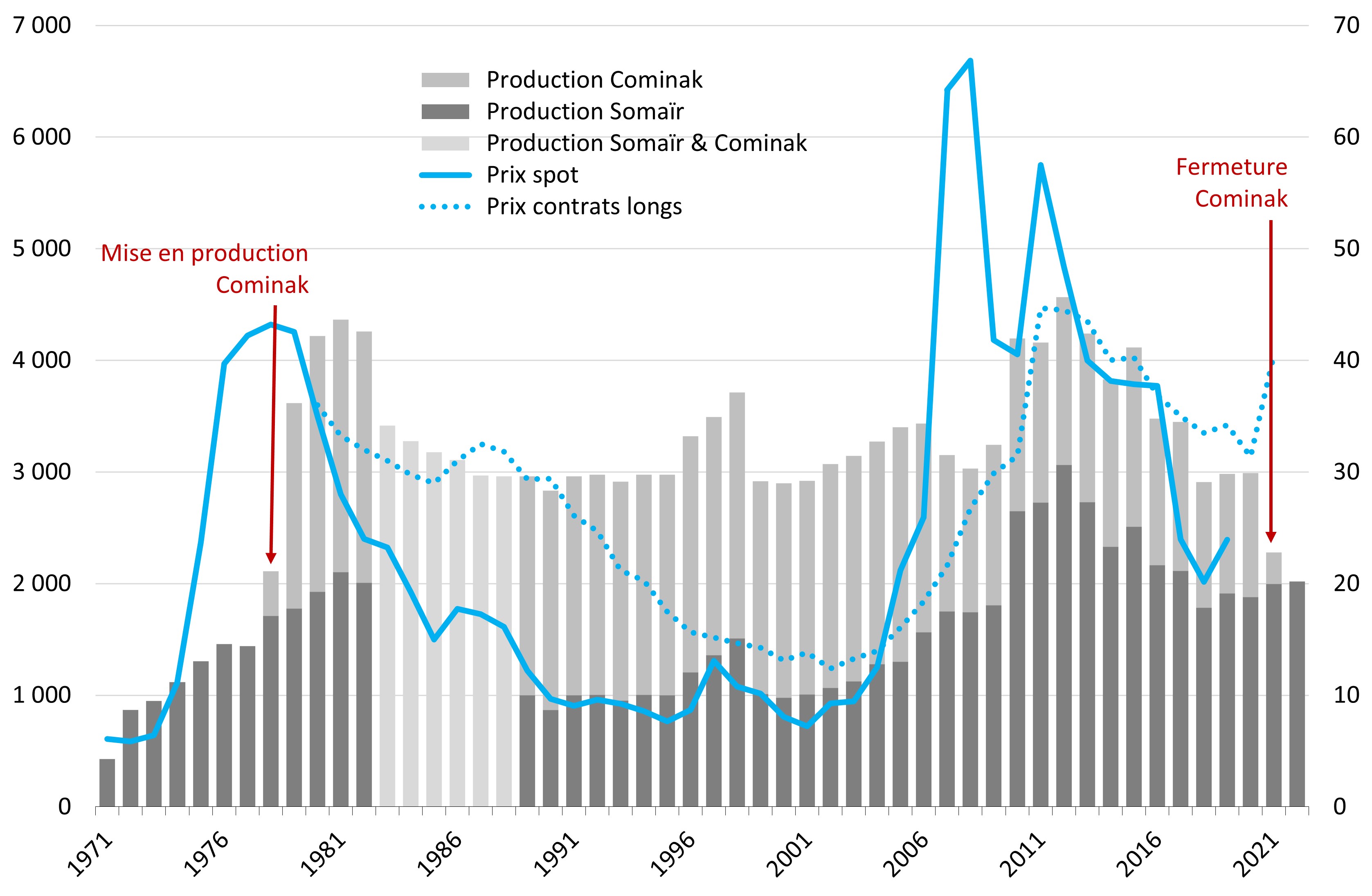

Since 1971 and the beginning of Arlit mine operations, Orano’s two subsidiaries in Niger, Societe des mines de l’Aïr (Somaïr), created in 1968 and Compagnie Miniere d’Akota (Cominak) created in 1974 have produced around 155,000 tons of natural uranium (see below), which is more than double the total production of French mines since World War Ⅱ (75,000 tons produced between 1954 and 2001, when the last mine in France was closed).

Sources. Production volumes: Annual reports of the secretariat of the Comité monétaire de la zone franc for the years 1971-1988, IMF Staff Country Reports for Niger for the years 1988-2001 and Areva-Orano annual reports for 2002-2022. Average annual spot price and average annual futures prices: Euratom Supply Agency, based on Nuclear Energy Agency and International Atomic Energy Agency, Forty Years of Uranium Resources, Production and Demand in Perspective, OECD, 2006. Spot price not calculated for 2020 and 2021 due to too few transactions.

After a rapid surge in the 1970s, annual production from Nigerien mines remained relatively stable, at around 3,000 tons, for just twenty-five years (1983-2009), with occasional peaks of up to 4,000 tons in the early 1980s and early 2010s, during periods corresponding to international uranium market spikes1.

When prices dropped, Somair’s production decreased as well, falling to around 1,000 tons. Conversely, production increases significantly during periods of rising prices (up to 3,000 tons in 2012). Cominak’s production, on the other hand, is less sensitive to price variations, remaining relatively stable from 1980 to 2005 (between 1,900 and 2,300 tons per year) before dropping to around 1,500 tons in the following decade, even when prices were high – perhaps to ‘preserve’ the deposit in a market context where Somair could take over. Production declined more sharply starting in 2015 until the mine was closed in 2021 due to resource depletion.

An overwhelming weight in foreign trade

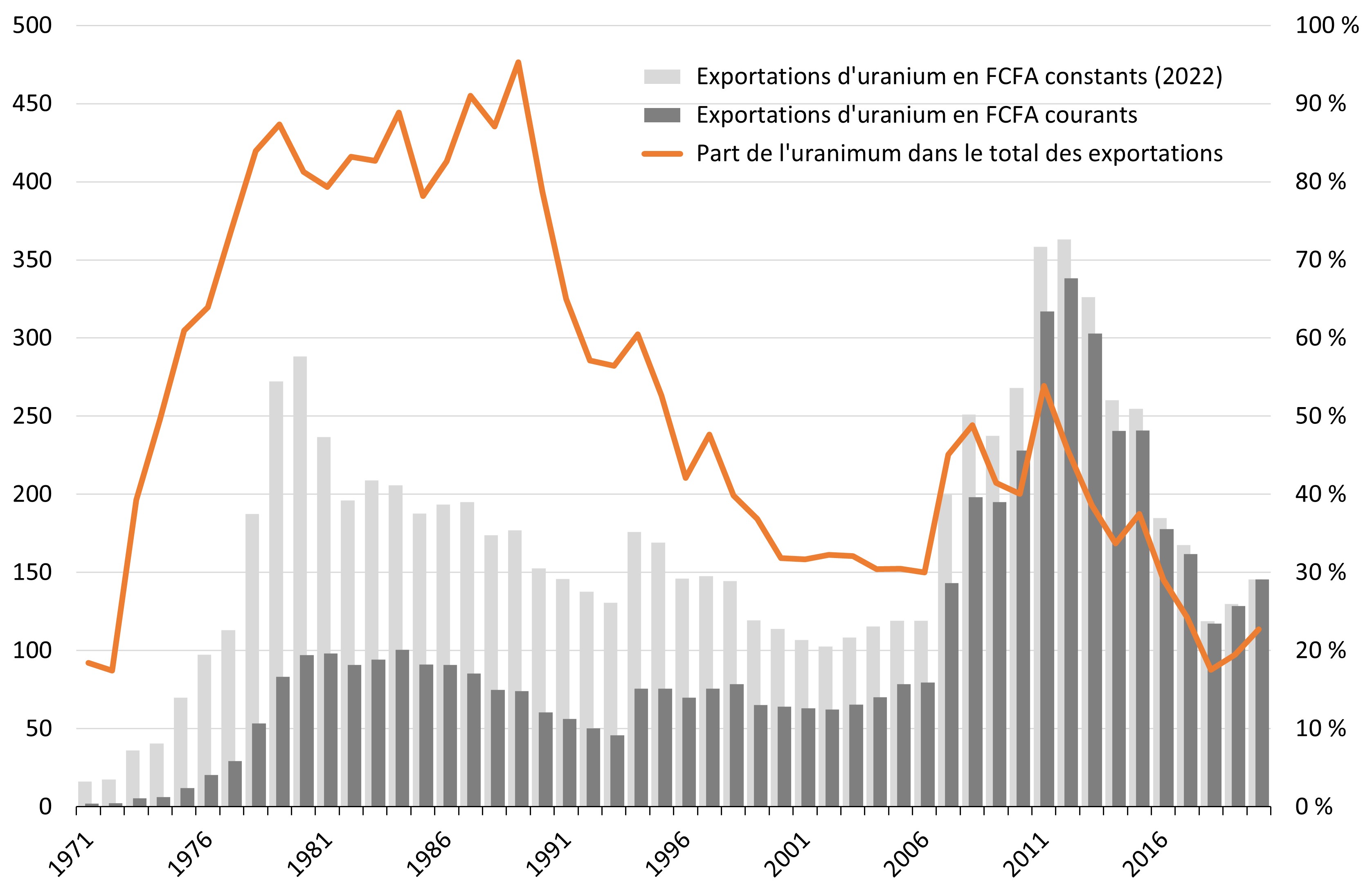

With such production volumes in an economy primarily based on agriculture, uranium quickly came to dominate Niger’s foreign trade. For over ten years, from 1978 to 1989, uranium exports accounted for more than 80 % of the country’s total export value (see below), making it especially vulnerable to the volatility of international market prices.

Sources. Uranium exports by value: BCEAO - Online economic and financial database for the years 1971-1991, Institut nigérien de la statistique for the years 1992-2020. Total merchandise exports (FOB) : World Bank. Average annual exchange rate : World Bank. Deflator : Calculation based on BCEAO for the years 1971-1989 and World Bank deflator for Niger for the years 1990-2020.

The stabilization of exported volumes, the decline in sale prices and Niger’s (relative) economic diversification gradually reduced this extreme dependence. By 2007, uranium represented “only” 30 % of the country’s exports. The rebound in the following years corresponded to the rise in international market prices and the increase in production volumes. In 2011, the “Yellow Cake” again accounted for more than Niger’s export balance. A final surge ? From that point on, the share of uranium in exports plummeted, driven by both a new drop in international prices and the start of oil production in Easten Niger in 2011. Today’s uranium accounts for 20 % and 25 % of Niger’s total exports.

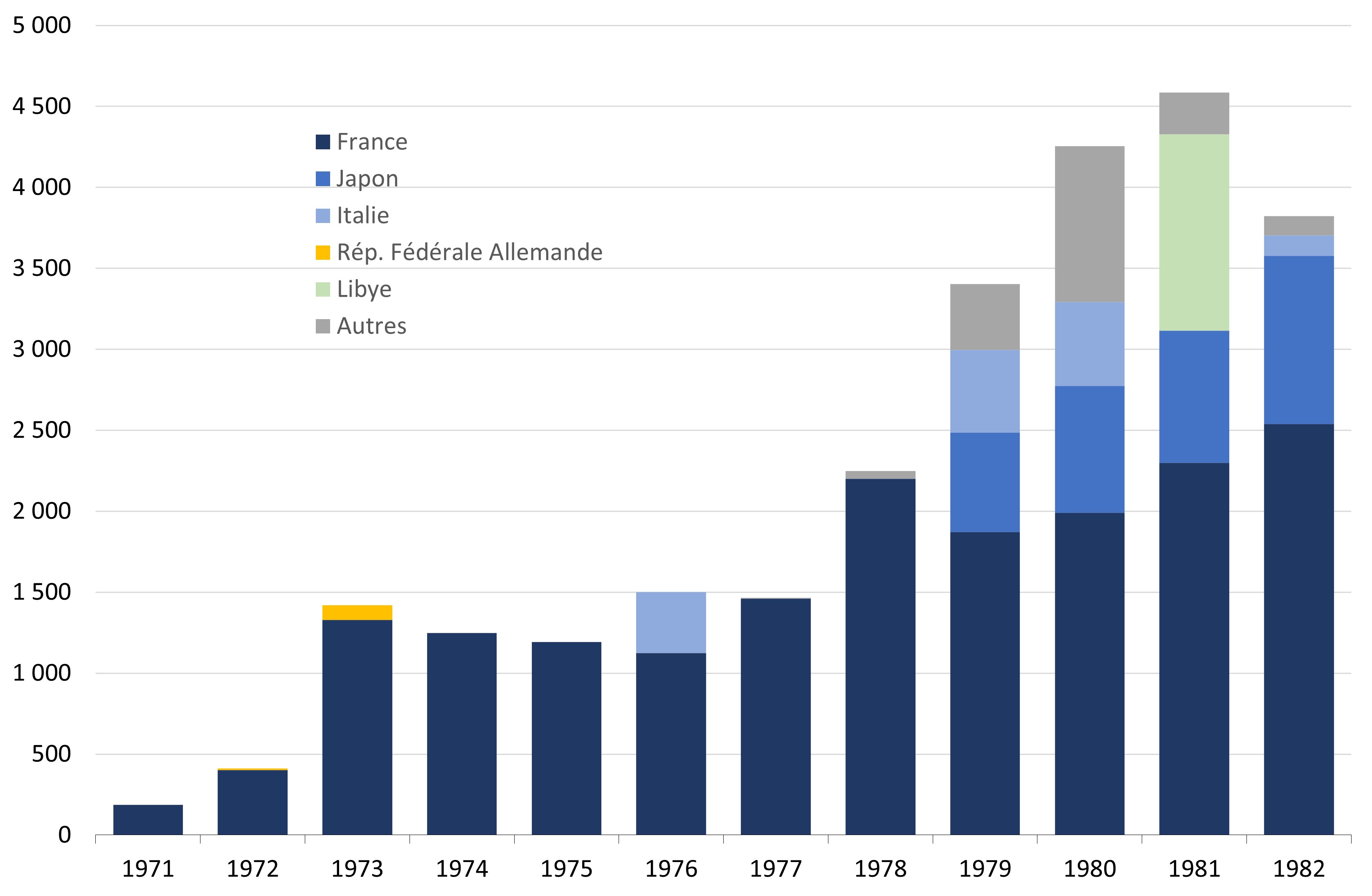

It is more difficult to determine with precision the destination of Niger’s production and the identity of the buyers. Until 1978, when Cominak opened, France captured almost all of Niger’s production, as it did with Gabon’s uranium2. Occasionally, other European countries benefited, like West Germany (91 tons in 1973) or Italy (375 tons in 1976).

Sources. Annual reports of the secretariat of the Franc Zone Monetary Committee for the years 1971-1982.

From 1979 onwards, exports to other countries, particularly Japan and Italy, became more significant. And for good reason, companies from the two countries became shareholders in Somair (Agip Nucleare, a subsidiary of Italy’s ENI, holding an 8.1 % stake) and Cominak (Overseas Uranium Resources Development Co.-OURD, a Japanese consortium, holding a 25 % stake). At the same time, France diversified its supply by turning primarily to apartheid South Africa (in 1978), which became a leading supplier, and Australia (in 1981).

The long battle over the «Niger price»

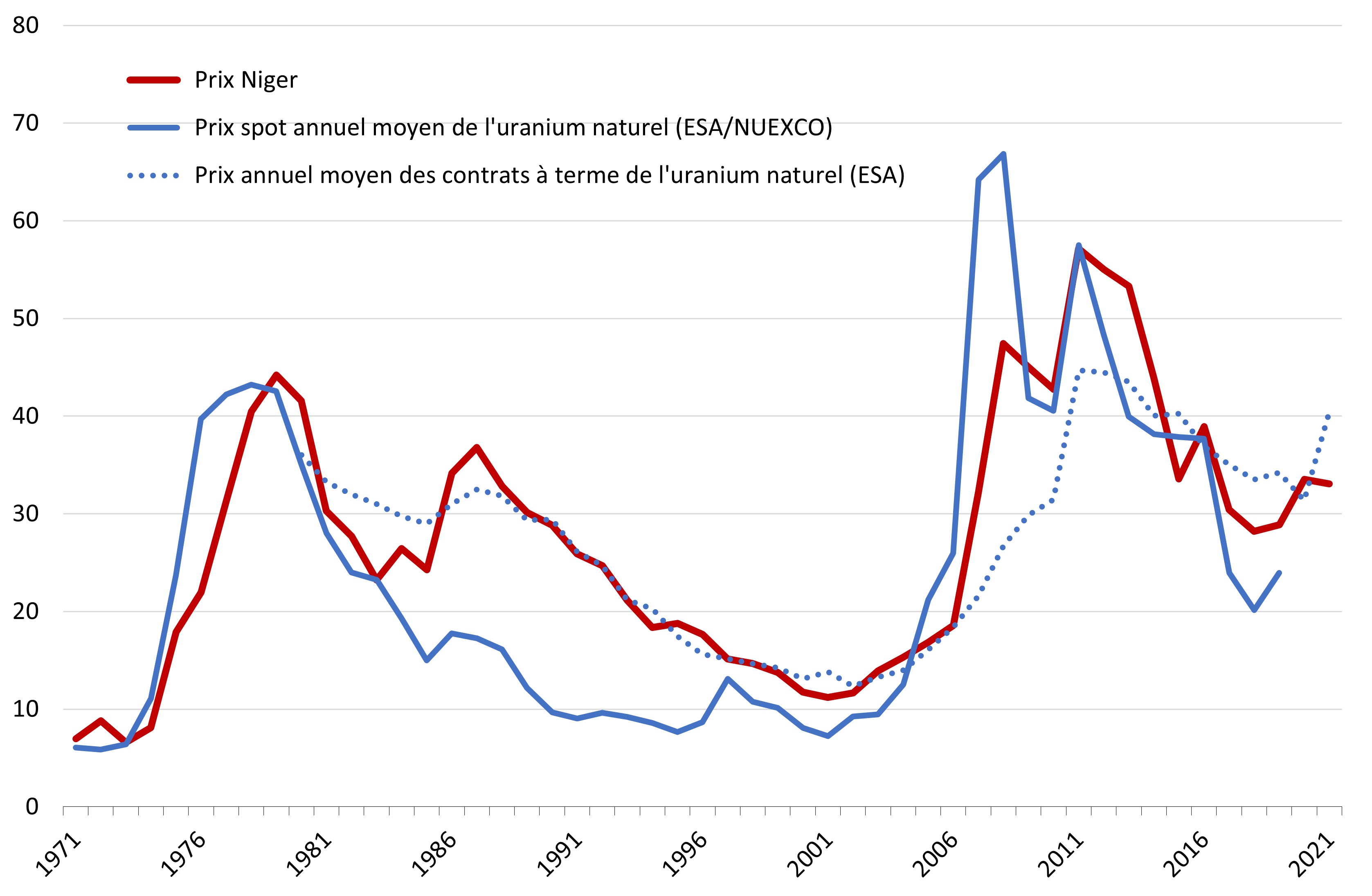

The “deal” between France and Niger regarding uranium has a particularity: the conventional price at which Nigerien uranium is sold by Somair and Cominak is negotiated annually within the companies ’boards of directors. This “Niger price”, as industry actors call it, is supposed to correspond to a “normal price by reference to the global market for comparable transactions”, according to the terms of the 1967 Franco-Nigerien uranium agreement.

Since the early years of production, Niger price has been one of the main sources of tension between the French multinational and its subsidiaries on one side, and the Nigerien government and civil society on the other. The reason is simple, it ultimately determines the amount that will accrue to Niger through mining royalties (calculated as a percentage of sales), corporate profit taxes (calculated as a percentage of Somair and Cominak’s profits), and the dividend s paid to shareholders (proportional to their shareholdings). The higher “Niger price”, the higher the state’s revenues. Therefore, it is essential to monitor the change of thus price and compare it to market prices-the “spot” price and the futures contract price.

By reconstructing the history of these prices, we can distinguish five periods (see below), each corresponding to phases of Franco-Nigerien renegotiations, sometimes very tense.

Sources. Uranium exports in value and volume: BCEAO - Online economic and financial database for the years 1971-1991, Institut nigérien de la statistique for the years 1992-2020, Annual reports of the secretariat of the Franc Zone Monetary Committee for the years 1971-1988, IMF Staff Country Reports for Niger for the years 1989-2006 and for the years 2007-2020, 2013 EITI report and BCEAO, Balance of Payments annual reports and Niger’s international investment position for sales (volume and amounts). Spot prices and forward contracts: Euratom Supply Agency, based on Nuclear Energy Agency and International Atomic Energy Agency, Forty Years of Uranium Resources, Production and Demand in Perspective, OECD, 2006. Spot price not calculated for 2020 and 2021 due to too few transactions. Average annual exchange rate FCFA / $ : World Bank.

During the first period (1971–1974), when only Somaïr was active, the “Niger price” was very low (around 5,000 FCFA francs per kg of uranium), as was the spot price. Everything changed in 1973–1974 when uranium prices soared on the international market due to the oil crisis. Nigerien President Hamani Diori, a figure of Françafrique close to Félix Houphouët-Boigny and Léopold Sédar Senghor, sought to negotiate a higher, ‘Niger price.’ He considered uranium not to be an “ordinary” commodity: “According to his reasoning, writes historian Gabrielle Hecht, if Niger’s uranium fuelled France’s exceptional nuclear capacity, then France could well provide an exceptional contribution to Niger’s public finances”3.

Diori demanded to index the uranium price to the price of electricity produced in France from oil – a measure his team claimed would raise the price per ton from 5.5 million CFA francs to 50 million CFA francs4. A standoff ensued between Niamey and Paris, culminating in Diori’s fall, overthrown in April 1974.

For a long time, it was believed that France, irritated by Diori’s demands, had supported the military coup to end the situation – especially since they had a military base in Niamey at the time. However, in 2014, historian Klaas van Walraven explored new, previously undisclosed archives that challenge this thesis : while it is true that the French were displeased with Diori’s demands and his rapprochement with Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, the Dutch researcher demonstrated that they “were not involved in the coup” and were, in fact, “completely taken by surprise”. The French even considered intervening to restore Diori to power but ultimately decided against it. Nonetheless, the “Niger price” was not raised to meet Diori’s demands. His successor, Lieutenant Colonel Seyni Kountché, was more accommodating and settled for aligning the “Niger price” with the spot price, which was rising sharply.

For nearly a decade, the “Niger price” fluctuated in line with the spot price, sometimes lagging behind by one or two years, both during the rising prices of 1973–1979 and during the price collapse starting in the late 1970s. A new shift occurred in the last years of Seyni Kountché’s rule, around 1983–1987, with a gradual decoupling of the ‘Niger price’ from the falling spot price. The “Niger price” then aligned with futures contract prices, which were more favourable during this depressed market period. This renegotiation received little attention but coincided with the signing of the first Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) with the IMF in 1983, compelling Niger to reduce public spending and increase revenue.

The “Niger price” then remained tied to the average futures contract price for nearly two decades, from 1988 to 2006. However, in the mid-2000s, as the spot price exploded on the international market, the situation became untenable for Niamey. A new standoff began between Areva and President Mamadou Tandja, who came to power in 1999. He leveraged the renewal of mining conventions for Somaïr and Cominak and Areva’s interest in the promising Imouraren deposit – a potential reserve of 200,000 tons that Areva did not want to cede to the Chinese – and secured a significant increase in the conventional price. Agreements in August 2007 and January 2008 confirmed an increase in the “Niger price” (40,000 FCFA francs in 2007, 50,000 FCFA francs in 2008 and 2009), breaking away from long-term contract prices to align more closely with the spot price.

Two years later, in February 2010, Tandja, who wanted to extend his time in power, was overthrown in a military coup. After a short transitional period, Mahamadou Issoufou was elected president. He happened to be a former Somaïr executive, having served as technical director at the end of the 1980s. His election coincided with the Fukushima disaster in Japan, which caused the spot price to plummet. Extremely tense negotiations ensued, leading to a new agreement in 2014, reached under murky conditions and amid accusations of corruption and embezzlement – what the Nigerien press termed the “uraniumgate”. From then on, the “Niger price” was determined by a formula reflecting the average of the previous year’s spot price and future prices.

Niger at the mercy of market prices

Thus, for five decades, Niger has endured the high volatility of natural uranium prices in the markets. Prolonged periods of low prices – far from the “value” Diori attributed to them during negotiations with Paris – have prevented it from benefiting significantly from the exploitation of this strategic mineral. Nevertheless, if we consider market prices as reference prices – though this does not imply they are “fair” – we see that the famous “Niger price” has remained relatively close to international market prices, as well as those negotiated with Somina, a Chinese company that operated the Azelik deposit in the early 2010s5.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that the outcomes of the multiple negotiations between Niamey and Paris have generally (though not always) favoured the Nigerien government, which has managed to index the evolution of the ‘Niger price’ alternately to the spot price and to future prices, depending on which option was least unfavourable for the country. The crux of the issue regarding low returns from uranium exploitation lies more in international market prices – over which the Nigeriens have little influence – and in mining taxation – which falls within their prerogatives – than in the “Niger price”.

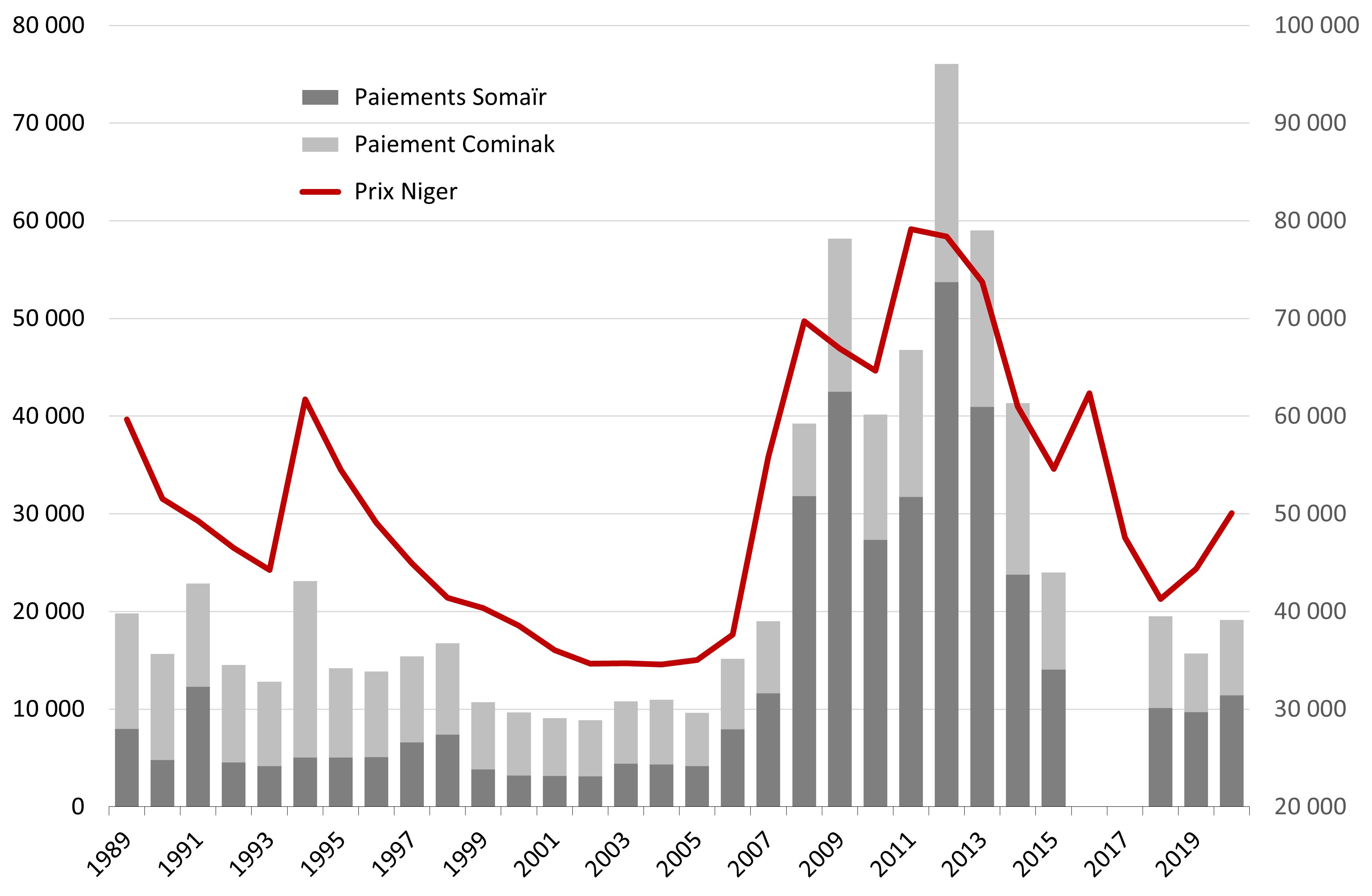

An examination of the contributions made to the Nigerien state by Somaïr and Cominak is particularly illustrative. The history of these contributions has been reconstructed for the past thirty years, from 1989 to 2020 (with two missing years, 2016 and 2017). Unsurprisingly, the number of annual payments is closely correlated with uranium selling prices, as these directly impact the mining royalties paid (4.5 % of exported value in the early decades of production, increasing to between 5.5 % and 12 % based on operating results since the 2014 agreement), the taxable base of profits made, and to some extent, export volumes. In constant 2020 CFA francs, the annual contributions from Somaïr and Cominak generally ranged between 10 and 20 billion until 2007, equivalent to 15 to 30 million euros (see below).

Source. Payments by company: IMF Staff Country Reports for Niger for the years 1989-2004 and 2007, EITI annual reports for the years 2005-2015 and 2019-2020, Somaïr and Cominak CSR reports for 2018. When, for the EITI reports, the declarations of payments differ between the State and the company, the State’s declaration after reconciliation is used. Calculation of the ‘Niger price’ : BCEAO - Online economic and financial database for the years 1989-1991, Institut nigérien de la statistique for the years 1992-2020, IMF Staff Country Reports for the years 1989-2006, 2013 EITI report and BCEAO, Balance of Payments annual reports and Niger’s international investment position for the years 2007-2020. GDP deflator for Niger: World Bank.

The increase in the “Niger price” from that date led to a significant rise in state revenues, peaking at 76 billion CFA francs in 2012 (116 million euros). The collapse of market prices thereafter resulted in a drop in contributions that the 2014 agreement failed to stem. They then returned, still in constant CFA francs, to their early 1990s levels.

The challenge of mining royalties

The renegotiation of the “Niger price” imposed by Mamadou Tandja in 2007, which decoupled it from long-term contract markets to bring it closer to the spot price, had a major impact on the level of Nigerien state revenue. However, these remain dependent on international price trends. The compromise reached with Areva has thus lost almost all of its effectiveness once prices fell; likewise, the agreements from 2014, which were supposed to allow Niger to earn more when uranium prices rose, had no effect on revenue levels during periods of low prices. Nonetheless, this fiscal lever remains the most interesting for Niger.

Thus, even a limited increase in the mining royalty rate – against which Areva/Orano has always opposed – would have significant consequences in terms of budgetary revenue. For instance, a mere two-point increase in this royalty (from 5.5 % to 7.5 %) would have yielded an additional 2 billion CFA francs for the state budget in 2021. If this increase had been applied since 2008, it would have added 43 billion CFA francs (66 million euros) to the state coffers.

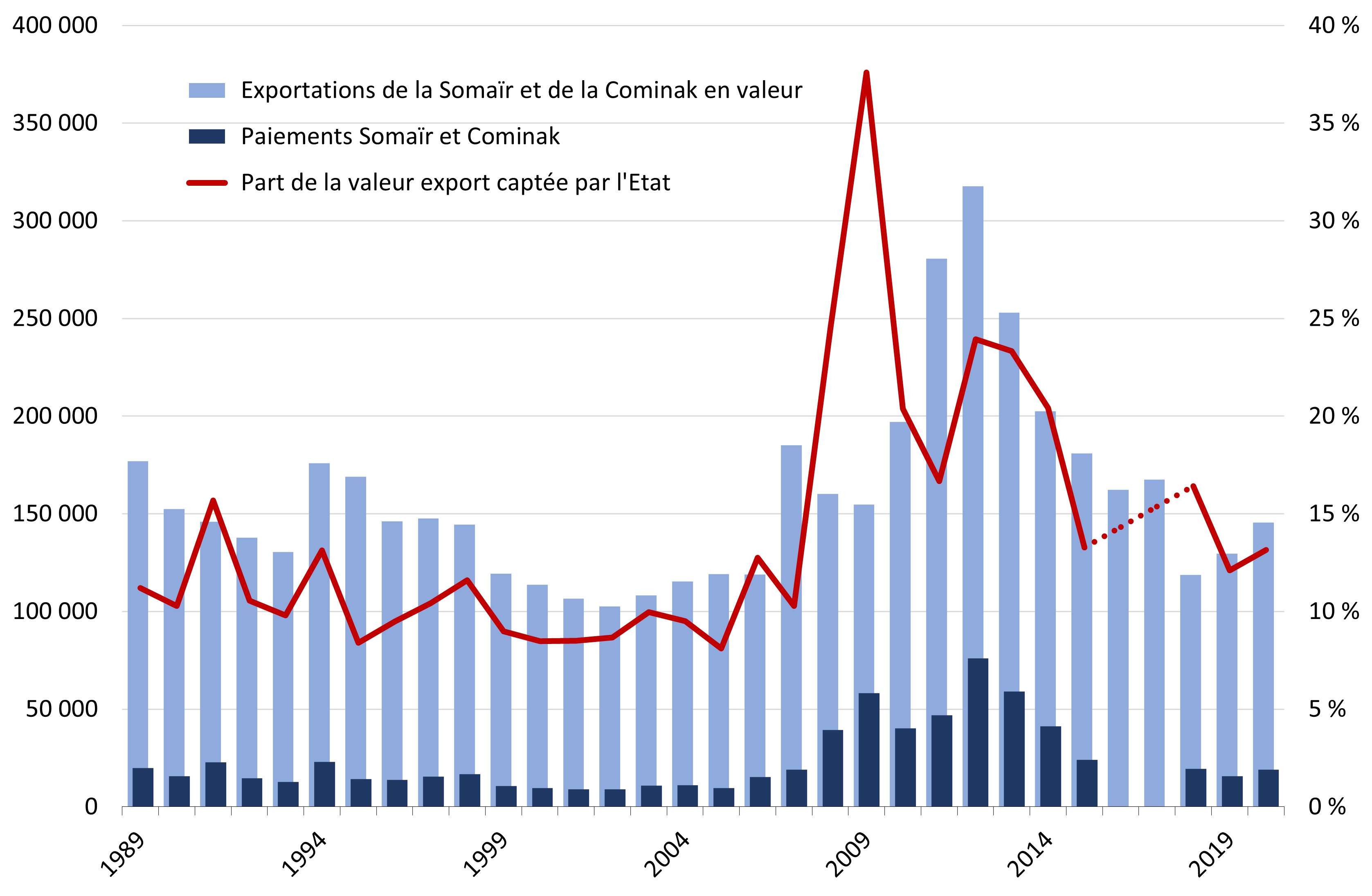

For Niger, the returns from exploitation are thus extremely limited6. From 1989 to 2020, Somaïr and Cominak exported nearly 100,000 tons of natural uranium, with a total value of around 5,100 billion CFA francs in 2020 (see below). During the same period, the Nigerien government received 760 million CFA francs in 2020, accounting for just under 15 % of the total (including payroll taxes and VAT). Notably, the years 2008–2014 alone represented nearly half of these contributions, due to exceptional market conditions. For the two preceding decades, the Nigerien state’s share was reduced to only 10.4 % of the total export value of Somaïr and Cominak.

Source. Payments by company: IMF Staff Country reports for Niger for the years 1989-2004 and 2007, EITI annual reports for the years 2005-2015 and 2019-2020, Somaïr and Cominak CSR reports for 2018. When, for the EITI reports, the declarations of payments differed between the State and the company, the State’s declaration after reconciliation is used. Value of exports: IMF Staff Country reports and Institut nigérien de la statistique for the years 1989-1999, EITI annual reports for the years 2000-2014 and BCEAO, Balance of Payments annual reports and Niger’s international investment position for the years 2015-2020. GDP deflator for Niger: World Bank.

These low returns are a constant for uranium-producing countries. Niger is not the worst off, though. In a study published in 2011, two Dutch organizations compared mining legislation in the uranium sector and its returns between 2005 and 2009 across four African countries: South Africa, Malawi, Namibia, and Niger; and for four mining companies: Rio Tinto, Areva, Paladin, and AngloGold Ashanti7. The findings showed that while budgetary returns from uranium exploitation were low for Niger, they were even lower for other African countries.

At that time, Niger appeared as the country with the heaviest taxation, having a higher royalty rate and a greater level of public participation in capital, especially with the state having the ability to sell directly, through the Niger Mining Heritage Company (Sopamin8), a significant portion of production. According to the report, for comparable production, revenues from uranium production in Niger were, during the period 2005–2009, 24 % higher than those in Namibia.

However, we are witnessing a “race to the bottom” – to borrow a phrase from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) - in the tax and regulatory competition among developing countries eager to attract or retain foreign investors, particularly in the mining sector. Being “less worse off” than its African competitors does not make Niger the “winner” of a fundamentally unbalanced relationship, serving the interests of the former colonial power.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism :

1Natural uranium market prices are generally expressed as spot prices or long-term contract prices, since most uranium purchases and sales are made under medium- to long-term contracts, which guarantee the buyer a delivery volume over time, at a price fixed in advance (although it may be partially indexed to the spot market). The spot price is theoretically volatile on a day-to-day basis; the futures price is less volatile, generally above the spot price in downturns and below it in upturns. This article uses the average annual prices of the Euratom Supply Agency (ESA), which are used as a reference by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

2Since 1961, a consortium of French companies known as Compagnie des Mines d’Uranium de Franceville (Comuf) has been mining Gabon’s Mounana deposit in the east of the country. Production reached around 1,000 tonnes a year from the early 1970s. The mine was closed in 1999.

3Gabrielle Hecht, Uranium africain, une histoire globale, Éditions du Seuil, 2016.

4Siradiou Diallo, “Hamani Diori : une chute surprise et ses mystères”, in Dossiers secrets de l’Afrique contemporaine, tome 1, Jeune Afrique-Livres, 1989.

5Somina’s selling prices are slightly higher, by 6-8 %, than those of Somaïr and Cominak, but for very small volumes (662 tonnes exported) and over a very short period of activity (2012-2014).

6The revenues received by the State represent only part of the economic spin-offs from mining, which also include the salaries paid to Nigerien workers, purchases and sub-contracting on the local market, and so on. However, the mining industry is capital-intensive (machinery, chemical inputs, etc.) but labour-intensive, which generally limits the benefits of mining for the national economy.

7Albert ten Kate & Joseph Wilde-Ramsing,“Radioactive Revenues. Financial Flows between Uranium Mining Companies and African Governments”, SOMO & WISE, 2011.

8Société du Patrimoine des Mines du Niger, created in 2007, manages the Nigerien state’s holdings in the mining companies operating in the country.