Special reports from Beni, Kasindi, Butembo, Mpondwe and Nobili.

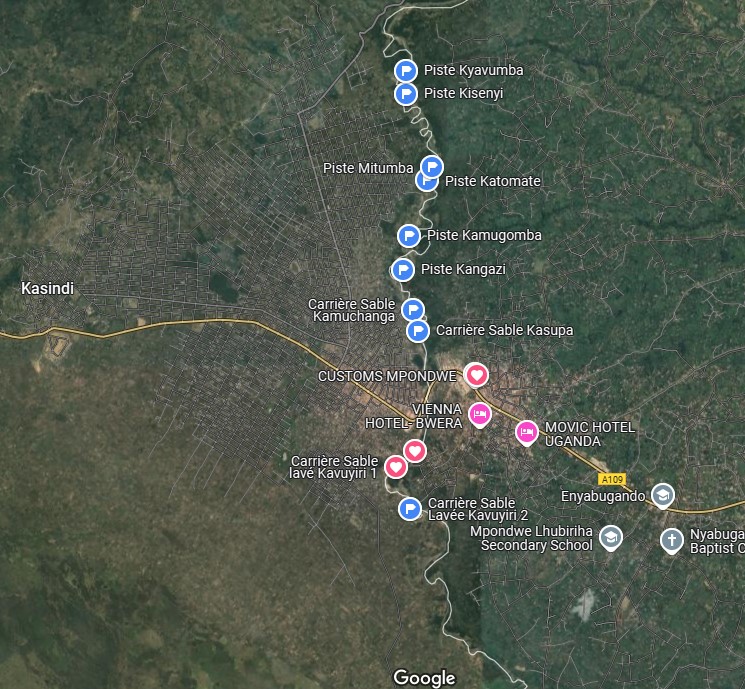

22 November 2024, North Kivu, in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Lubiriha River is at its lowest. The river separates the two towns of Kasindi-Lubiriha in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Mpondwe in Uganda. At this time of year, the two banks are separated by little more than thirty metres of water. The surrounding area is heavily guarded by the Forces armées de la RD Congo (FARDC) and the Uganda People Defense Forces (UPDF). Contrary to what might be expected of these two national armies, their objective is not to control but rather to facilitate the crossing of hundreds of people and tonnes of goods, which thus evade customs controls. Day and night, the traffic takes place under their eyes and with their blessing in exchange for money. Cocoa beans are one of the main products smuggled.

Cocoa is DRC’s leading agricultural export. According to the World Bank1, the country exported some 63,971 tonnes of beans in 2023, generating $50 million in taxes, according to data from the Central Bank of Congo (BCC). The ninth largest exporter in Africa, DRC was also the second largest exporter of organic cocoa to Europe (the world’s largest customer) in 2023, with 8,061 tonnes.

Since 2023, the world price of cocoa has continued to break records, driven by poor harvests in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana (the world’s leading producers) due to climate change. The price (2) tripled in 2024, reaching $11,675 per tonne on 31 December 2024. Under these conditions, the brown gold is more coveted than ever. Armed groups, which abound in eastern DRC where the vast majority of Congolese beans are produced (particularly in the Beni region), and exporters, prepared to do anything to increase their profits, are vying for this financial windfall. This business fuels corruption among public officials and exacerbates insecurity.

For several months, Congolese journalists from the Ukweli Media Hub Coalition, an investigative platform specialising in the Great Lakes region, have been working on the ground, in partnership with Afrique XXI and Africa Uncensored. Their observations in the field, their interviews (often anonymous for security reasons) and the documents they obtained have revealed the scale of this trade, which is worth several million euros a year and whose main victims are small-scale producers and the Congolese tax authorities.

The soldiers take €0.59 per bag

To cross the Lubiriha river, the goods are carried on the heads or backs of young people, who are generally unemployed. They receive small sums of money for each parcel transported. “For each 100 kg bag of cocoa, we have to pay 2,000 Congolese francs (€0.59) to our country’s soldiers and 1,000 shillings (€0.23) to the Ugandan soldiers,” explains Jacques (not his real name), a vehicle washer and occasional handler we met on the Kamuchanga trail, not far from the customs post. The owner of the cocoa pays us 1,000 or 1,500 Congolese francs to get his goods through. We can pass up to ten bags a day each", he concludes.

The owner negotiates the deal as early as possible with the soldiers at the nearest post. Meanwhile, the cargo remains in illegal warehouses in Kasindi-Lubiriha, in private homes, on building sites or in officially recognised warehouses. During this investigation, Ukweli was able to observe the ballet of vehicles, belonging to at least one recognised operator in the region, which transport hundreds of kilos of cocoa with the complicity of the FARDC and the UPDF. For obvious security reasons for journalists, his name cannot be divulged.

“The authorities are aware of the smuggling being carried out by this gentleman, but nobody dares to talk about it, because it also involves the local security services,” says a local chief who wished to remain anonymous. “Do you think that a large shipment of cocoa like this could be fraudulently exported without any government department knowing about it?”

State agents involved at all levels

When contacted by Ukweli, Major Bilal Katamba, Communications Officer at the Ugandan Ministry of Defence and Veterans’ Affairs, denied any direct involvement of Ugandan soldiers in the illegal trade (see “Behind the scenes” box). For his part, Mak Hazukay, deputy spokesman for the FARDC, denied in April on Radio Okapi 3 that Congolese soldiers were involved in any trafficking between the region and Uganda.

During a work visit to Kasindi-Lubiriha on 20 December 2024, Alain Bavidila, deputy director of the Directorate General of Customs and Excise in Beni (DGDA, the main customs anti-fraud brigade), called on local residents to “strongly support the Kasindi DGDA by denouncing any attempt at fraud in the various porous paths [sic] along the Lubiriha river within the authorised services”, reported local media (4).

This appeal contrasts with the behaviour of its agents in the field, who have become the prime enablers of smuggling. “Other large quantities of smuggled cocoa pass directly through customs thanks to a network essentially made up of state agents,“says one of the exporters interviewed by Ukweli. “Customs officials lower the export tax per kilo from 0.5 to 0.3 dollars [0.43 to 0.25 euros] or offer exporters lump sums regardless of the quality or quantity of the product. And then there are the priceless volumes transported in small quantities by cars and tricycles.” On 23 November 2024, on the Kyavuyiri 1 runway, local agents from the Congolese National Police, the National Intelligence Agency, the DGDA and the Congolese Control Office intercepted four cars carrying several bags of cocoa destined for the Ugandan informal market. Rather than seize the goods, they split the $600 fine between them before allowing the cargo to continue on its way, according to a witness who witnessed the operation.”It’s a very common practice", says a sand farmer who owns a quarry located just between FARDC and UPDF military positions, and who therefore watches smuggled goods pass from one bank to the other.

5 to 10 tonnes a day sold in Uganda

”Most of the fraudulent exporters and importers have protection in Goma or Kinshasa," says an anonymous police source who has been stationed in the region for five years. “When a commander is newly appointed and wants to put an end to their trafficking, they [the various officers involved, editor’s note] demand that he be transferred. As a result, the local authorities are forced to make do with this mafia in return for thousands of dollars, luxury cars and even plots of land.”

On the other side of the border, in Uganda, the Mpondwe Cocoa Market is flourishing. This market is mainly supplied by smuggled Congolese cocoa. “Around 5 to 10 tonnes are sold here every day,“explains one of the traders in charge of the market, who believes he is talking to suppliers. “To avoid several taxes, our Congolese customers use fraudulent routes by paying small sums to the military. We then send three-wheeled motorbikes to collect the goods from the river. Once there, we discuss the price. The advantage we have here is that we can sell at a higher price than in DRC”, he continues, also offering financial services.

Fraud enables Congolese producers to obtain a better price for their beans, and buyers to avoid the administrative complications and associated costs. In DRC, the export procedure is long and costly. According to an internal document from the National Office for agricultural products (Onapac), it costs at least $10,000 to obtain a licence to export cocoa.

Young people are stealing cocoa

To finance these clandestine exports, private companies and individuals based in Uganda pour millions of dollars or Ugandan shillings in cash into the sector. The money flowing in cash increases insecurity in the region, as complicit Congolese economic operators sometimes cooperate with bandits. Well-known companies such as Esco Kivu (based in Uganda and DRC), the leading exporter of cocoa beans in the region, contribute to this circuit, according to several eyewitness accounts and concordant documents consulted.

In several towns in North Kivu and Ituri, some young people have started stealing cocoa. They disguise themselves as fighters from the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) or operate in small independent armed groups, armed with machetes and sometimes guns. They injure or kill the owners of the cocoa trees before stealing their produce. This is known as the “tentera” phenomenon, which means “to slip” in Kinande, a local dialect.

These attacks force farmers to abandon their fields. In Beni, in the Sayo district, “more than fifty farmers died in their fields in April 2024”, according to the local civil society. Officially, these killings are attributed to the ADF, but eyewitness accounts suggest that local groups are disguising themselves with the complicity of soldiers and intelligence agents. This version is rejected by the military intelligence commander in Beni. Contacted by Ukweli, Colonel Delphin points to ADF fighters and local youth groups disguised as ADF. According to him, the proof can be found in the videos of his department’s interrogations that Ukweli was able to consult.

In them, people described as former ADF fighters and collaborators, but also former hostages of the jihadist group, claim to have taken part in the looting, theft and marketing of cocoa. These confessions confirm other testimonies gathered by Ukweli from other former rebels.

Stolen cocoa beans are sold in their “wet” state. Yet the provincial authorities prohibit the marketing of cocoa in its wet state. Still even officially recognised export companies buy them. Such as the Union for Traders of Agricultural Products in Congo (Uneproac), an association that has been based in the centre of Sayo since December 2024.

“Armed men strangle and kill farmers”

Anyone who tries to expose this mafia-style system is exposed to threats and reprisals. In 2024, an agronomist and state agent who tried to have an illegal buyer of wet beans arrested, received a death threat from Muhindo Katavali, the government intelligence agency ANR’s head of office in Mulekera, as shown in a message obtained by Ukweli. In the message, the sender introduces himself as “the head of the ANR/Mulekera” and “warns” him about his “attempts to destabilise the service at the border/Sayo”, concluding that “a man warned half-heartedly is enough” (sic). Ukweli listened to several similar audios.

Despite these threats, local activists are not prepared to keep quiet. A member of a farmers’ association in Beni expressed his indignation:

The district chief, the police and the army are opposing the bans issued by the governor, who is their boss! We pay taxes for these people, and now they’re allowing the purchase of wet beans from our cocoa trees. They steal at night and all day long they display their stolen products.

He was speaking at a meeting organised in Beni in December 2024, which Ukweli was able to attend. Another exasperated farmer said: “We are almost being fought by everyone. We are scared, but we are willing to die for our children’s future. These wet bean buyers have already weakened all the authorities through corruption.” “In the plantations in Masau, Mununze and Makene [Ituri province, editor’s note] the situation is complicated,” says Tigre Kambale, a cocoa buyer based in Mambasa. “Armed men are strangling and killing farmers. Last time, one of them ended up cutting up three bandits on his plantation with a machete.”

“I was forced to deny it”

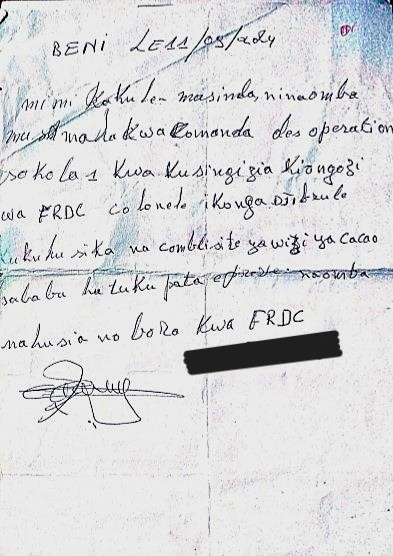

Ukweli’s investigation was able to shed light on the extent to which the forces of law and order were involved in this trafficking, as in the case of a senior officer deployed to the area in April 2024 to fight the ADF. Colonel Ikonga Djibrule was quickly accused of involvement in cocoa trafficking, in collusion with certain soldiers in his unit and civilians, some of whom were armed. The cooperative for the development of agricultural producers in Congo, a local association, then denounced his actions. In response, the officer had its president, Masinda Kamangura, arrested, accusing him of “slanderous denunciation”.

Detained and tortured for several days by Beni military intelligence, he was forced to retract their statement in a letter (see above), dated 11 September 2024.

“[The deputy commander] forced me to retract a letter that my association had sent to the sector command denouncing the behaviour of soldiers who were stealing our produce," he says. “He threatened to do the same to me as to Alain Siwako (5) if I refused [a member of parliament arrested for alleged collaboration with armed groups, known in the region for his courage in denouncing FARDC abuses, editor’s note]. I had to sign a discharge that wiped out the denunciation of his behaviour by around sixty people… [who had all supported the letter, editor’s note]”, he explains.

Accused of “slanderous denunciation” against an FARDC officer, Masinda Kamangura was transferred to the Beni garrison. Later, magistrate Bazila Nyembo, who was in charge of the case at the Beni prosecutor’s office, advised him to give up and offered to close the case on condition that he paid a sum of money to avoid conviction for slander.

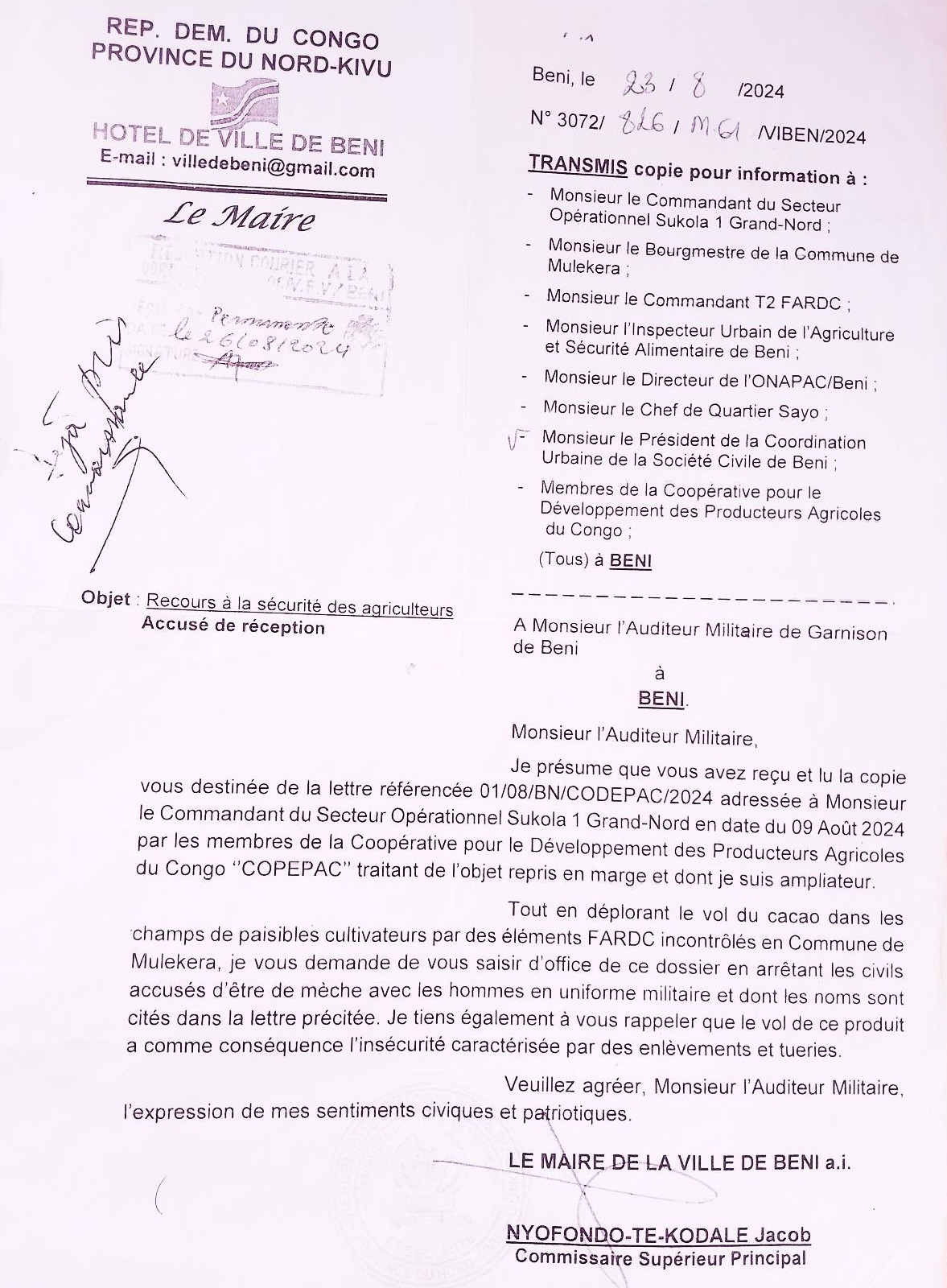

In August 2024, Senior Superintendent Jacob Nyofondo-Te-Kodale, the mayor of Beni, decided to get involved and ordered the arrest of civilians who were FARDC accomplices in the cocoa theft. At the same time, changes occurred in the security forces and the judiciary, including different positions for the senior officer involved and the military auditor of the Beni garrison. But no sanctions were taken. And the mayor’s letter (opposite) remains unanswered by the head of the military justice in Beni to this day.

Small arrangements in exchange for “motivation costs”

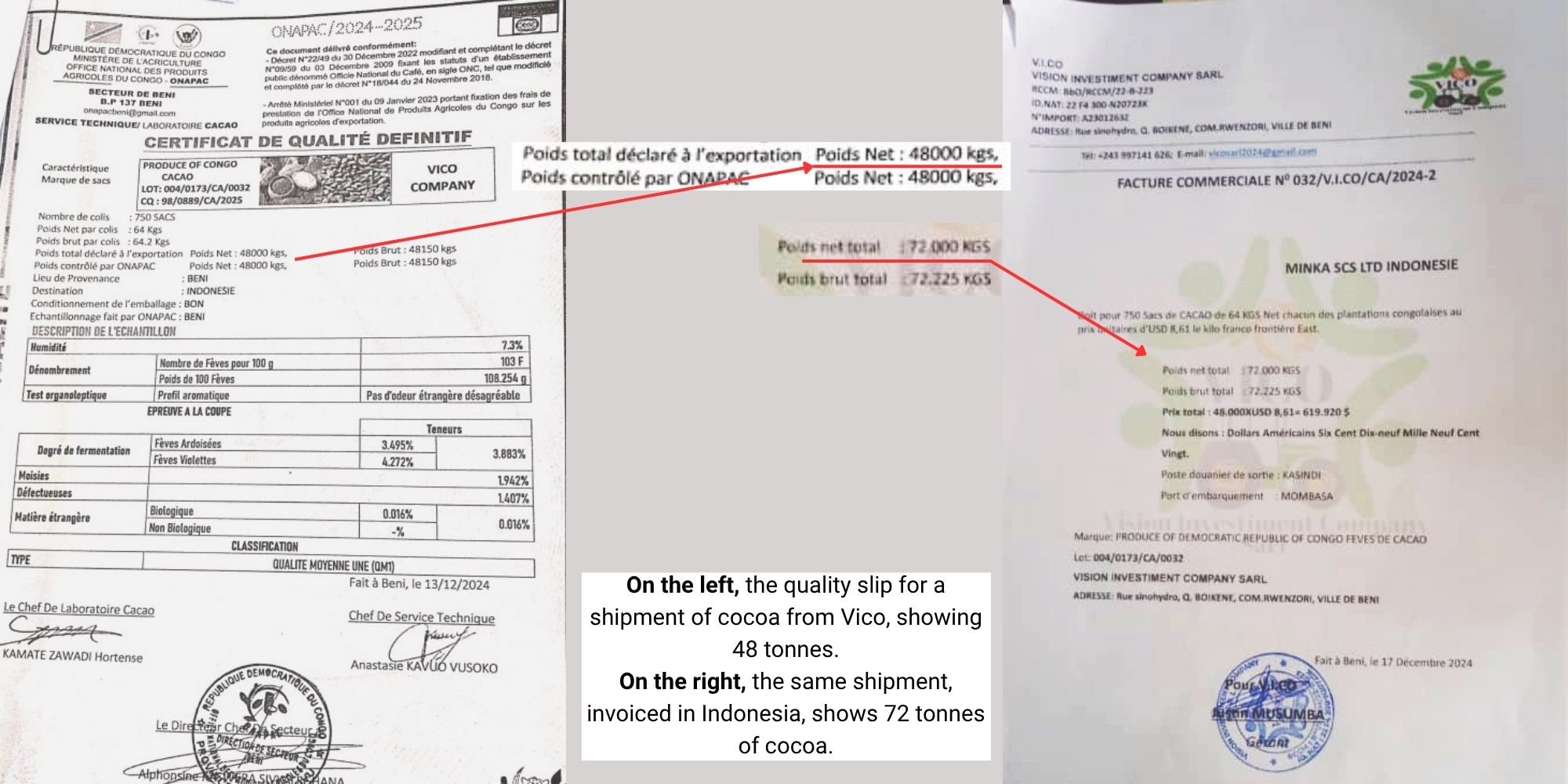

The fraudulent export of cocoa also involves well-known companies. Official documents consulted by Ukweli were falsified to underestimate the actual volumes exported. On 13 December 2024, the company Vico declared 48 tonnes of cocoa for export to Indonesia, according to Onapac. However, several documents issued by the Congolese Office for Control (test report, dispatch note, etc.) show 72 tonnes. According to our calculations, these 24 tonnes of difference cost the Congolese government some $12,000 in lost taxes. None of the actors involved could provide an explanation for these inconsistent figures, claiming that they were confidential matters. Threats were even made to dissuade Ukweli from insisting.

This is not an isolated case in the cocoa industry. According to an anonymous source at Onapac, in November 2024, MC Compagnie attempted to export 72 tonnes of cocoa, declaring only 50 tonnes. The shipment was intercepted by Onapac in Beni. The company cited an error that had been reported to the relevant departments beforehand, but failed to provide any proof. MC Compagnie was initially suspended by Onapac on suspicion of fraud, and its export licence was withdrawn. However, unnamed sources within the organisation claim that the company was once again authorised to export a few weeks later, following an undisclosed compromise.

In the field, Congolese officials receive bribes, known ironically as “motivation fees”. These practices make it easier to falsify documents and underestimate the tonnages of products to be exported. According to our source at Onapac, several officials have been dismissed after agreeing to be “motivated” to facilitate smuggling, confirming the extent of corruption within the public services.

During this investigation, all the entities implicated were officially contacted. Most did not wish to comment or simply did not reply, while others openly threatened the journalists who were investigating.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism: