It is 1976. The Cold War is in full swing. Officially liberated from colonialism for about fifteen years, African countries are fueling the appetite of the Western and Soviet blocs. After an enchanting interlude and the wind of hope that the independences had stirred, the end of the 1960s gives way to a disenchanted future: Mali, Algeria, Burkina Faso, Benin, Congo... Military coups are succeeding one another. In Togo, a former French colony, a military man has been leading the country since 1967. His name: Gnassingbé Eyadéma. He is the guide of the Togolese people’s revolution. The providential man with mystical powers. A former wrestler from a poor family who came to power thanks to his intelligence. There are not enough superlatives to describe him: an erudite and affable soldier trained by France, a patriot who saved the country from anarchism and the communist threat. Only God is above him... This laudatory portrait –that is an understatement– of the Togolese putschist Eyadéma is not the work of the author of this article.

This ode comes from a comic book titled “Il était une fois… Eyadéma” (“Once upon a time… Eyadema”). Behind this story is a publishing house named ABC, or Afrique Biblio Club. In 1976, ABC launched “Il était une fois…”, a collection of comics about the history of the “fathers of the nation” of many African countries. The first one was dedicated to Eyadéma. Others quickly followed: Mobutu (DR Congo, 1977), Hassan II (Morocco, 1979), Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast, 1979), Ahidjo (Cameroon, 1980), Gaddafi (Libya, 1980), Bongo (Gabon, 1980), and even Duvalier (Haiti, 1980).

The ABC adventure relies on a well-structured organization. At the head of the publishing house, we find a duo of complementary leaders. Jean-Louis Gouraud, former head of the Culture department of “Jeune Afrique magazine” (and a great specialist in horses and riding...), who has a significant address book on the continent, and Alain Gouttman, a historian of the Second Empire and Napoleon, which in a way serves as a guarantee in the hagiographic treatment of the characters. On the editorial side, we find the screenwriter Serge Saint-Michel, who has worked alongside the greatest comic book authors, including René Goscinny, the creator of the Asterix and Obelix adventures.

Paid in copper and sheep

Dominique Fagès, for his part, had the heavy responsibility of illustrating the features of the collection’s heroes. “I never met the heads of state involved,” he told Afrique XXI. “I don’t know Africa and I’ve never been there, so the publisher provided us with piles of agency photos of Eyadéma, Mobutu, or Gaddafi...” The cartoonist was 27 years old and just started out in the profession.

I was happy to have work, but it’s true that looking back, it’s crazy! At the time, I was fresh out of school, looking for a job. I wanted to do comics but could not find anything, and I landed this gig by chance... It was still published by Casterman, which is no small thing...

Casterman, a huge Belgian publishing house specializing in comic books with Hergé’s The Adventures of Tintin at the forefront. While no capital link is known between Casterman and Afrique Biblio Club, some of the comic books in the collection were printed in Tournai, in the premises of the Belgian publisher. A sign that the company was not skimping on resources to satisfy their African clients...

Half a century later, Dominique Fagès still has a tarnished image of her former employers: “They were actually mercenaries of publishing. They made luxurious books. I remember they got paid for the book about Eyadéma in copper and sheep…” And for the scripts, the recipe was quite simple: to romanticize the rise to power of these future dictators, to retrace their journey by telling the story of men who sacrificed everything for the good of their nation. Dominique Fagès adds:

I was not responsible for the storyline, which was always the same from one album to the next. An African captain in the French army takes power legitimately and becomes friends with French presidents. That’s “Françafrique.” France, a friend of Africa, which supported dictatorships.

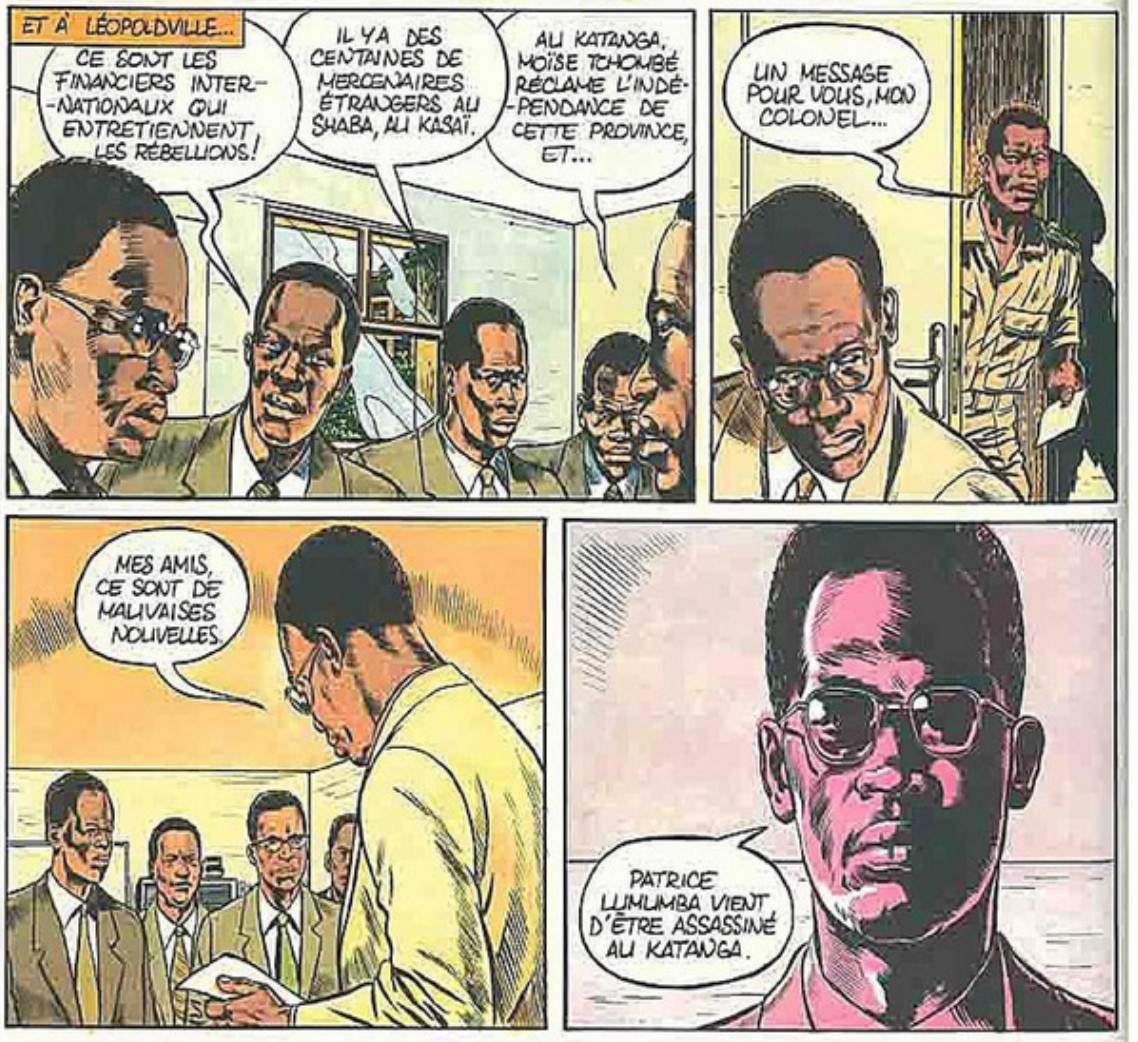

Dominique Fagès drew the comics of Eyadéma, Mobutu, and Gaddafi. It was necessary to be productive: “The bar was very high; you had to be very efficient and go very fast without asking questions. In terms of the drawings, it was a real performance…”, he recounts. Fifty years later, he still remembers the historical absurdities of the scenarios. “In the Mobutu comic, it was written that the future president of Zaire [which became DR Congo in 1997, editor’s note] learns of Patrice Lumumba’s death by telephone, even though we all know he was involved…”, he explains.

As a result, the reality is less glorious… The Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was killed in 1961 by the United States and Belgium, with Joseph Mobutu as a puppet, who would become Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa Za Banga during the “Zairianization” of the country in 1971.

“It is manipulation, it is propaganda!”

The last character that Dominique Fagès drew was Muammar Gaddafi, with, there too, a rewriting of history. “There was a kind of intellectual endorsement saying that Gaddafi was a great guy. I was starting to get tired of doing that...” And then, one day, Dominique Fagès learns that the book about Eyadéma was distributed free of charge in Togolese schools. “At that moment, I felt a sense of guilt. I was totally manipulated. I learned a lot in drawing technique, but in terms of conscience it is terrible. Nevertheless, fifty years later, I curiously remember that I learned my trade,” he explains, fatalistically, before making a daring comparison:

They weren’t selling weapons, but this thing is still a weapon because it’s propaganda distributed to people who haven’t had an education... It is disgusting, it is manipulation, it is propaganda! But at the time we weren’t aware of it since they were friends of France.

He is then offered to draw Bokassa, but he refuses and decides to put away his pencils for this endeavor.

Meanwhile, ABC launches another collection in Africa called “Je connais” (I know) (name of the country). In the volume dedicated to Cameroon, one can read language elements straight out of French colonial semantics. It refers to “terrorist acts” triggered in 1956 by the Union des populations du Cameroun (UPC) to describe the independence rebellion. It is specified that its leader, Ruben Um Nyobe, was killed on September 13, 1958, by “a patrol of law enforcement,” meaning French military forces.

The rewriting of history? “I have no comment”

For his part, Jean-Louis Gouraud, one of the publishers but above all one of the thinkers behind this collection, explains that he created these comics with the aim of connecting Africans with their history. “I had done a collection of pocketbooks called Great African Figures with my friend the historian Ibrahima Baba Kaké,” he told Afrique XXI. ’I could clearly see that Africans had a great demand for the history of the continent and its great figures, so I decided to make comic books for younger people.’ Regarding the rewriting of the characters’ lives, he fully assumes responsibility and even goes on to explain it by the authoritarian nature of these regimes:

You know, all these countries still operated under content surveillance regimes. I have nothing to say about that. All countries, even the most ’democratic’ ones, exercise surveillance over historical content.

But how much money did this adventure bring him? Jean-Louis Gouraud gives no figures but confirms Dominique Fagès’ statements: “Naturally, there was a financial contribution in the sense that the governments that accepted had to buy a certain number of copies from me for distribution in schools.”

The adventure ends in 1980. In total, sixteen flattering portraits of African presidents were published over four years in the collection “Il était une fois...”. These books will not remain in posterity, but they have the merit of being witnesses to an era when France, “Africa’s best friend,” had an uninhibited complacency with dictatorial regimes.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism: